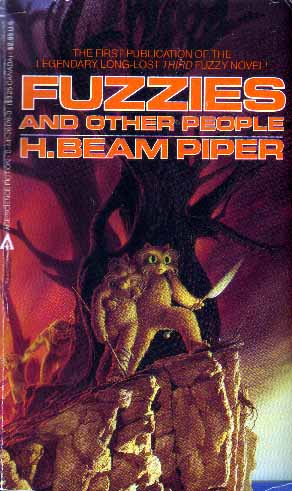

Little Fuzzy (1962), Fuzzy Sapiens (1964) and Fuzzies and Other People (1984—but written in 1964) don’t seem to be exactly in print. Little Fuzzy can be purchased with a pile of H. Beam Piper’s other stories for the Kindle for 80 cents, an offer so good I can hardly believe it, but the other books don’t seem to be available at all. Well, there are plenty of copies around second hand. These are classics. They’re also charming, and have aged surprisingly well.

They’re part of my favourite subgenre of SF, the kind with planets and aliens. The books fit into Piper’s Nifflheim universe but all they need is each other. Zarathustra is a recently settled planet run by the Chartered Zarathustra Company as a Class III planet, one without native intelligent life. Jack Holloway, an independent sunstone prospector, discovers what he at first takes to be an animal and calls it a “Little Fuzzy,” and then realizes it is a member of an intelligent species—or is it? The very interesting question of the sapience of the Fuzzies, who don’t qualify under the “talk and build a fire” rule of thumb, takes up the rest of the book. The evil company will lose control of the planet if it has intelligent natives. There’s a court-case—it’s surprising how little SF has climactic court cases. This is a terrific one, funny, exciting, and ultimately triumphant.

It’s interesting to consider that date of Little Fuzzy, 1962. There’s a line in the book where a hotel is reluctant to admit Fuzzies and the lawyer “threatens to hit them with a racial discrimination case” and they immediately back off. In 1962 there were still hotels in parts of the US that didn’t admit people of all human skin colors. In some US states, people of different skin colors weren’t even allowed to marry, never mind South Africa. Martin Luther King was campaigning, the civil rights campaign was in full swing, and Piper, a white man who loved guns, frontiers, and history, chose to write about a world where these questions were so settled—and in the liberal direction—that everyone’s arguing about the civil rights of aliens and he can throw in a line like that. There’s also the question of the “childlike” Fuzzies, who have a protectorate for their own good. There’s no doubt Piper knew exactly the history of such protectorates when applied to humans other humans called “childlike” and took into their paternal protection. Holloway calls himself “Pappy Jack” for a reason.

In Fuzzy Sapiens, (and I guess the name is a spoiler for the first book!) the company turns out not to be so bad, putting together a planetary government turns out to be really difficult, and some bad people try to exploit the Fuzzies. Fuzzies are sapient, but they’re at the level of understanding of a ten- to twelve-year-old child. And they have problems with reproduction which needs human science to cure. And here Piper goes head on with a species that really does need protection, that really does need things “for their own good,” that is sapient but may not be responsible, and the difficulties of dealing with that. The answer for the Fuzzies is that they are becoming symbiotes, giving the humans something the humans want as much as the Fuzzies need what the humans can give them. That’s Fuzzy fun—and the question of whether you can get that from human children (though they do grow up…) is left aside. People want to adopt Fuzzies, and the word “adopt” is used. But what can you do if you have a whole species of sapients who are about as responsible as a ten-year-old child? We don’t have any real sub-sapients on Earth, but Piper made up the Fuzzies and made them cute and made a thought experiment that doesn’t have simple answers.

It’s Fuzzies and Other People that really lifts the series out of the ordinary, because for the first time we have a Fuzzy point-of-view. The novel follows a small band of Fuzzies who have had no human contact, as well as Little Fuzzy lost in the wilderness, and the usual human cast. The Fuzzies have agency. They are figuring out the world. They aren’t as simple as they look. When humans have taught them tricks, like making a fire or a spear, they’re more than ready to use that for their own purposes. (There’s a lovely line where Little Fuzzy is making a spear and remembers that the humans have said to use hand-made rope but he doesn’t have time so he’ll use some wire he has in his bag…) They’re still charming and innocent and childlike, but in their own internal point of view they have dignity. The book ends with a group of Fuzzies going off to Earth. I wish Piper had lived to write the books that would have come after and shown Fuzzies in the wider universe.

Piper also gets points for feminism and for cleverly using the reader’s implicit (1962) assumption of anti-feminism against them. There’s a female scientist in the first book who also turns out to be a Navy spy, and nobody suspects her, even when she thinks “a girl in this business ought to have four or five boyfriends, one on every side of the question.” My instinctive reaction to that is always “Ugh!” but it’s an “Ugh” that a lot of early SF has conditioned me to expect. When it turns out she’s a spy, why, that makes perfect sense. The pool of stenographers is as old fashioned as the viewscreens, but I think that comes under “they have an FTL drive but no iPods and everyone still smokes.” You can’t really complain about that kind of thing. All the women we see have jobs, many of them have scientific jobs, and when we see a woman sentenced in court she gets the same sentence as the others. 1962? Pretty good.

I think a lot of Piper’s best work was at short story length, but I think these are a terrific set of short novels. I didn’t read them when they were first published (I wasn’t born until a month after Piper died!) but in 1984 when the first two were republished at the time of the publication of the third. So I was twenty, not twelve, and they were already twenty years old, but they charmed me to pieces. They still do. My son read then when he was twelve, and promptly read the rest of Piper. (He especially liked Space Viking, also available in that astonishing 80 cent Kindle bundle.) These are still deeply enjoyable stories. Nobody writes things like this any more, so it’s just as well we’ve still got the old ones and they’re still good.